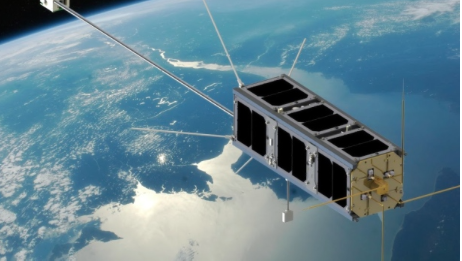

The Ex-Alta 1, a small "cube" satellite similar to this one, was constructed by a team of students at the University of Alberta. (Supplied)

A not-so-funny comedy of errors didn't keep this satellite designed by a group of students at the University of Alberta from capturing data from a huge solar flare. Here's their story.

A tiny made-in-Edmonton satellite began beaming messages back to Earth just in time to capture the most powerful solar flare in more than a decade.

The Ex-Alta 1, designed by a group of students at the University of Alberta, has survived extreme radiation, computer crashes and nail-biting mechanical glitches during its maiden voyage through space.

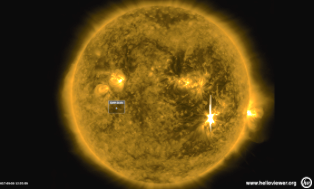

But when a massive solar flare erupted from the surface of the sun last week, spewing radioactive plasma towards Earth, the satellite was ready to capture data from the explosion.

'Quite the scientific punch'

The superpowered "X-Class" flare was the strongest recorded in 12 years, but the cube-shaped satellite was perfectly suited to observe the storm.

"When these big, big clouds of energy-released, charged particles come off the sun, they take about three and a half days to come off the Earth, so you have some fair warning," Tyler Hrynyk, flight operator with Ex-Alta 1, said in an interview with CBC Radio's Edmonton AM.

"We got our warning and we made sure we were in mission control and ready."

A powerful solar flare erupted on the surface of the sun Wednesday, disrupting radio communications. (Helioviewer/NASA)

Orbiting Earth at an altitude of 400 kilometres, the satellite — no larger than a loaf of bread — is engineered to capture data on extreme space weather.

With a design that allows for high-frequency measurements of the Earth's magnetosphere and thermosphere, the satellite is studying powerful forces such as solar flares, which can threaten spacecraft, satellites, and essential electronic networks on Earth. The U of A is then sharing its measurements with research hubs around the globe.

"Despite being that small, it packs quite the scientific punch," Hrynyk said.

"It wants to study how solar flares and other charged particles interact with our atmosphere … things like the very beautiful natural phenomena like the northern lights or how it can damage ground infrastructure, knocking out electronics and things like that.

"We're trying to study that relationship a little bit more."

Technical difficulties

The 40 undergraduate students who designed the satellite over the course of four years have been anxiously tracking its movement through the stars, and it hasn't exactly been a smooth ride.

The battery started draining at an alarming rate and the team was forced to send a software update to remedy the problem.

Another bug plagued the mission in mid-June. The computer system kept going off and on repeatedly, without warning.

Overwhelmed with radiation, the system finally shut itself down, went into reboot, and "saved itself."

Despite the recent turbulence, Hrynyk and his team remain confident the satellite can stay in orbit until the end of its mission in 2019, when it will slowly fall back toward Earth and lose contact with its creators.

"Anomalies, we've had a few of them, they're unavoidable," Hrynyk said. "Every single space mission is going to have anomalies, because you can't go up there and fix it after you've sent it out.

"But what separates your space mission from others is how you deal with those anomalies and we've dealt with all of them."