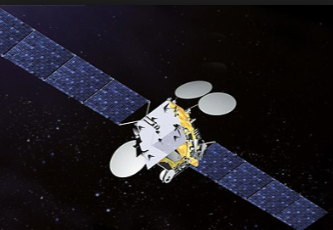

Telkom 3S [Thales Alenia]

Taking the learning very seriously, the Indonesian engineers are aiming to develop their own satellites.

Indonesia is taking baby steps to reduce its dependence on foreign telecommunications satellites through technology-transfer arrangements and micro-satellite development.

In fact, more and more Indonesian engineers have been trained abroad to master the technology.

A 27-year-old engineer from state-owned telecommunications company Telkom, Angga Risnando, for example, has learned the art of making the Telkom 3S satellite directly from Cannes-based satellite manufacturer Thales Alenia Space (TAS).

“I learned for one-and-a-half years specifically about [satellite] payloads. I learned from people who are experts in designing transponders,” he told during a media visit to the TAS factory in Cannes, France, on Friday.

The Telkom 3S satellite, scheduled to be launched this week from French Guiana in the northern part of South America, will support the company’s voice and data services.

To transfer the knowledge he received from his overseas internship, Angga wrote a number of books he passed on to his colleagues in Telkom.

With more engineers trained abroad, a glimmer of hope is arising that Indonesia can build its own commercial satellites to provide telecommunications services for its population of 250 million people.

“Indonesia currently needs 300 transponders, 140 of which are our own while the remaining 160 are rented [from other parties].” Telkom’s chief technology officer Abdus Somad Arief said in Cibinong, West Java, recently.

He said the archipelagic country, which consists of 17,000 islands, could be fully independent of foreign satellites in the future since the country’s space agency, the National Institute of Aeronautics and Space (LAPAN), had successfully launched locallymade micro-satellites.

So far, the space agency has launched three experimental satellites in India, namely LAPAN A-1/Tubsat in 2007, LAPAN A2/ Orari satellite in 2015 and LAPAN A3 in 2016.

LAPAN’s experimental satellites are different from the operational satellites launched by state lender Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI), telecommunications operator Indosat and Telkom in terms of weight, price and function.

Micro satellites developed by LAPAN are worth between Rp 35 billion (US$2.63 million) to Rp 65 billion each and weigh less than 100 kilograms. They are positioned at a lower orbit and are used for observation such as monitoring land usage or ship movements, LAPAN head Thomas Djamaluddin told the Post.

Meanwhile, an operational satellite costs around Rp 3.5 trillion, weighs 3.5 tons, is positioned at geostationary orbit and can be used for improving telecommunications services and broadcasting.

According to LAPAN’s roadmap, it will take more than 25 years to develop operational satellites due to budget constraints.

This year, the government has allocated Rp 698 billion for LAPAN, down from Rp 777 billion a year before. The budget cut has forced the space agency to postpone buying components and expanding its laboratory in a bid to develop satellite technology.

Realizing these obstacles, Thomas said the strategy was that after LAPAN finished creating two more experimental satellites, the A4 and A5 in 2020, it would start creating small operational satellites weighing between 500 to 1,000 kg.

“Our strategy after building A5 is that we are going to create operational micro-satellites, because that is the best thing to do in terms of budget and time for preparation,” he said.

Apart from budget constraints, another challenge faced by the agency is the government’s regulation on the moratorium of civil-service requirements. The moratorium makes it harder for LAPAN to find competent engineers to develop locally-made satellites.

At present, LAPAN only has about 30 engineers who specialize in satellite manufacturing working at its technology center in Rancabungur, Bogor.

Thus, to accelerate the process of creating satellites on its own, LAPAN — like Telkom — regularly sends some of its engineers overseas to learn about the satellitemaking process.

“We will send around 10 engineers to develop their knowledge in satellite-making to Japan, Korea and some countries in Europe this year,” Thomas said.