An artist's impression of the Zhangheng I electromagnetic surveillance satellite to be launched next year. Photo: Handout

The destruction from a major earthquake can create havoc not only with buildings but with the emotional, physical and financial burdens it leaves on people.

Beijing and Taipei will join hands in space to monitor the electromagnetic signals that can precede earthquakes following a landmark intergovernmental agreement last month.

The agreement, reached by the governments on both sides of the Taiwan Strait, will see the mainland give Taiwan partial access to data collected by an electromagnetic surveillance satellite it will launch next year. In exchange, Taiwan will share some of its data with the mainland.

An electromagnetic surveillance satellite is a reconnaissance satellite equipped with advanced sensors that can intercept extremely weak radio signals. The data it collects can be used for civilian purposes, for example the study of electronic disturbances in the upper atmosphere caused by earthquakes and volcanic activity, but can also have military applications, such as identifying the location of radar stations, missile launch facilities and other hidden defence assets.

Some earthquakes emit electromagnetic waves before they occur and scientists hope to collect and study those signals to further the development of earthquake forecasting.

The intergovernmental project, to be funded equally by Beijing and Taipei, was launched last month at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Remote Sensing and Digital Earth in Beijing, a statement posted on the institute’s website said.

Professor Jann-yenq Liu, the Taiwanese side’s lead project scientist, said its focus on studying earthquakes would bring numerous benefits to Taiwan.

A rescuer looks for survivors after a building collapsed when a magnitude 6.4 earthquake struck Tainan, in southern Taiwan, in February last year. Photo: Xinhua

The mainland’s new satellites would carry a wide range of sensors that were better than those on similar satellites launched by other countries, he said.

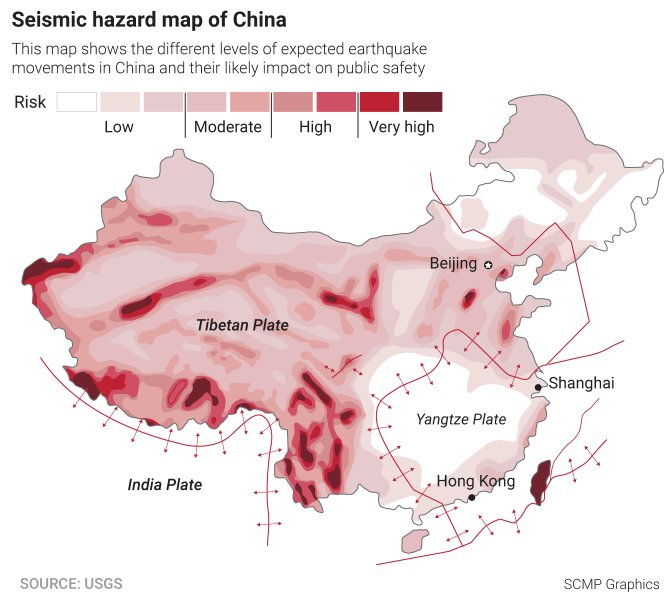

Taiwan sat on some active fault lines and faced a high risk of destructive earthquakes. If abnormal electromagnetic signals could be picked up by a satellite hours or days before an earthquake, lives could be saved and economic losses minimised.

“We have seen rapid advancement of technology in recent years, and the new satellite will collect a large amount of valuable data,” Liu, from the Graduate Institute of Space Science at National Central University in Taoyuan, said. “The hope of achieving earthquake forecasting is higher than ever before.”

The mainland and Taiwan would be equal partners in the project, he said, contributing matching amounts of data, and researchers from other countries would also be involved.

Liu said the satellite’s instruments might pick up some militarily sensitive signals such as radar beams, but “to us these man-made signals are noise”.

“They must be removed to reveal the signals produced by nature, which is what we are looking for,” he said.

Li Zaoshe, an associate researcher with the academy’s Institute of Electronics in Beijing who designs surveillance devices for military satellites, said electromagnetic surveillance was an extremely sensitive area due to its military applications.

A chart at Taiwan’s Seismological Observation Centre in Taipei following a magnitude 5.8 earthquake that occurred 19.7km off the coast of Yilan, in northeast Taiwan, in May last year. Photo: EPA

“This is the first time. I have never heard of cooperation of any form in this field with Taiwan before,” he said. “This kind of data is usually classified.”

A researcher at the Centre for Taiwan Studies at Fudan University in Shanghai said the launch of the project might signal a bilateral effort to ease cross-strait tensions.

Political dialogue between Beijing and Taipei stalled after the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party’s Tsai Ing-wen defeated Kuomintang candidate Eric Chu Li-luan in the island’s presidential election in January last year. Anti-mainland sentiment on the island then rose when Beijing reduced the number of mainland tourists allowed to visit Taiwan and circled the island with nuclear bombers.

“The mainland extended an olive branch and Taiwan accepted it, but both sides have kept it quiet because the ice is still far from thawed,” said the researcher, who requested anonymity due to the political sensitivity of the project. “The mainland also has increasing confidence about the technical superiority of its military assets. The mainland military may know Taiwan better than their counterparts on the island.”

An official at the Straits Exchange Foundation, a semi-official organisation set up by the Taiwanese government to handle technical or business matters with the mainland, said the two sides had reached intergovernmental agreements before on trade and disaster prevention.

But the agreement on electromagnetic surveillance was more sensitive and would likely involve the military in Taiwan, the official said.

Taiwan’s defence ministry declined to comment.

The mainland’s new electromagnetic surveillance satellite is expected to be launched into a near-Earth orbit early next year. It will be the first member of a multi-satellite constellation that should be able to cover the globe by 2020.

The new satellites will be named after Zhang Heng, a polymath in ancient China as famous as Leonardo da Vinci in Europe. Zhang, a statesman in the Eastern Han Empire nearly 2,000 years ago, made notable achievements in a wide range of areas, from astronomy, mathematics, engineering and geography to art and poetry.

One of his most notable inventions was the “earthquake weathervane”, an instrument recorded in historical texts that was able to detect a tremor hundreds of kilometres away and point out the rough direction of its epicentre.

The Zhangheng satellites will operate at an altitude of 500km, with each one completing a scan of the Earth in less than two weeks. When the network is complete it will allow researchers to detect and trace electromagnetic signals to their origin at any location on the planet.

Chen Xiaobin, a researcher at the China Earthquake Administration’s Institute of Geology, said using a satellite to forecast an earthquake was difficult because some earthquakes did not emit radio signals.

“No one can fully explain why some earthquakes are preceded by electromagnetic disturbances and some are not,” he said. “We don’t really understand the physical mechanism behind these phenomena.”

Chen said Taiwan’s participation in the Zhangheng project was a “relatively recent” event and its access to data would be limited.

Military facilities such as radar stations produced high-frequency radio waves, he said, while those generated by an earthquake tended to occur at lower frequencies, although there could be overlaps in some cases.

“The data will be graded according to its sensitivity; each grade accessible to only users with matching clearance,” Chen said.

The new satellites were initially proposed by mainland scientists as a purely civilian project for earthquake studies, with the first Zhangheng satellite originally scheduled for launch in 2009, a year after a large earthquake killed more than 70,000 people in Sichuan province.

But the project suffered severe delays, in part because the mainland government wanted to use the satellites for other purposes including meteorology, mapping, geology and military applications.

A 17-storey apartment building collapsed when a magnitude 6.4 earthquake struck Tainan in southern Taiwan in February last year. Photo: EPA

The Battlefield Environment Support Bureau, a special unit at the headquarters of the People’s Liberation Army, will be among the first to receive the data from the new electromagnetic surveillance satellite, according to a project document posted on the website of the China Earthquake Administration in August.

The bureau operates directly under the Joint Staff Department of the Central Military Commission. One of its functions is to gather and analyse electromagnetic intelligence in areas targeted for military operations.

China has already established a global surveillance network using large, sophisticated reconnaissance satellites, including the Shijian and Yaogan series. Their capabilities are classified but are believed to include optical and radar sensors.

But the Zhangheng series, using the latest technology, will be considerably smaller and cheaper, making a quick mass launch possible.

The United States and Europe have launched similar satellites for earthquake studies, with Demeter, a micro-satellite launched by France in 2004, observing an increase of electromagnetic waves a month before a big earthquake struck Haiti in 2010. But the many technical challenges encountered led to those projects being discontinued.