Small enough to fit inside a backpack, RainCube (Radar in a CubeSat) uses experimental technology to see storms by detecting rain and snow with very small instruments.

The people behind the miniature mission celebrated after RainCube sent back its first images of a storm over Mexico in a technology demonstration in August. Its second wave of images in September caught the first rainfall of Hurricane Florence. The small satellite is a prototype for a possible fleet of RainCubes that could one day help monitor severe storms, lead to improving the accuracy of weather forecasts and track climate change over time.

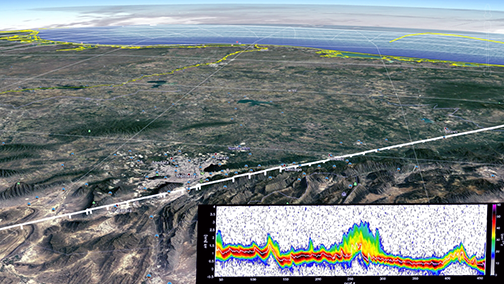

A photo from Google Earth of the mountainous area over Mexico where RainCube measured its first storm. The white line shows RainCube's flight path. The colorful graph in the bottom right shows the amount of rain produced by the storm, as seen by RainCube's radar.

Image is courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech/Google.

RainCube is a type of "tech demo," an experiment to see if shrinking a weather radar into a low-cost, miniature satellite could still provide a real-time look inside storms. RainCube "sees" objects by using radar, much as a bat uses sonar. The satellite's umbrella-like antenna sends out chirps, or specialized radar signals, that bounce off raindrops, bringing back a picture of what the inside of the storm looks like.

RainCube was deployed into LEO from the International Space Station in July. The first images it sent back were from an area above Mexico, where it took a snapshot of a developing storm in August. But RainCube is not meant to fulfill a mission of tracking storms all by itself. It is just the first demonstration that a mini-rain radar could work.

Because RainCube is miniaturized, making it less expensive to launch, many more of the satellites could be sent into orbit. Flying together like geese, they could track storms, relaying updated information on them every few minutes. Eventually, they could yield data to help evaluate and improve weather models that predict the movement of rain, snow, sleet and hail.

Artistic rendition of the RainCube satellite. Image is courtesy of NASA/JPL.

And that future seems closer now that RainCube and other Earth-observing cubesats like it have proven they can work. RainCube is a technology-demonstration mission to enable Ka-band precipitation radar technologies on a low-cost, quick-turnaround platform. It is sponsored by NASA's Earth Science Technology Office through the InVEST-15 program. JPL is working with Tyvak Nanosatellite Systems, Inc. in Irvine, California, to fly the RainCube mission.

Executive Comments

Graeme Stephens, Director of the Center of Climate Sciences at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said the organization doesn't have any way of measuring how water and air move in thunderstorms globally — yet, it's so essential for predicting severe weather and even how rains will change in a future climate. JPL will actually end up doing much more interesting insightful science with a constellation rather than with just one of them. What is being learned in Earth sciences is that space and time coverage is more important than having a really expensive satellite instrument that just does one thing. What RainCube offers on the one hand is a demonstration of measurements that are currently available in space today. But what it really demonstrates is the potential for an entirely new and different way of observing Earth with many small radars. That will open up a whole new vista in viewing the hydrological cycle of Earth

Engineers such as Principal Investigator Eva Peral had to figure out a way to help a small spacecraft send a signal strong enough to peer into a storm, who said that the radar signal penetrates the storm, and then the radar receives back an echo. As the radar signal goes deeper into the layers of the storm and measures the rain at those layers, we get a snapshot of the activity inside the storm.

Simone Tanelli, the co-investigator for RainCube, noted that there's a plethora of ground-based experiments that have provided an enormous amount of information, and that's why weather forecasts nowadays are not that bad. However, they don't provide a global view. Also, there are weather satellites that provide such a global view, but what they are not stating is what's happening inside the storm — that's where the processes that make a storm grow and/or decay happen.