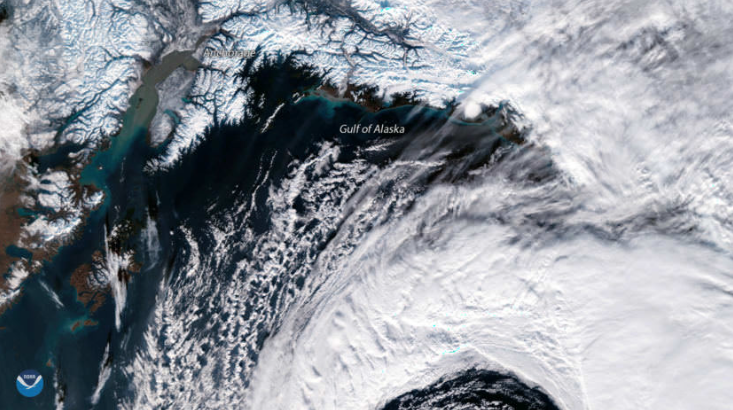

A large area of low pressure moves through the Gulf of Alaska in this image from the Suomi NPP satellite, taken on November 6, 2017. The storm generated gale warnings for the south central and southeastern portions of the state. (Image courtesy NOAA/Environmental Visualization Laboratory)

A new satellite will help predict Alaska’s weather and warn of natural hazards, much earlier and with better accuracy.

Called JPSS-1 as the first in the Joint Polar Satellite System, the next-generation satellite features instruments that can see through clouds, determine sea surface temperatures, detect rising river levels, and spot small fires before they become big ones.

The Earth rotates as the satellite orbits from pole-to-pole at an altitude of 512 miles. That means the satellite takes new, close-up pictures of the Earth during each hour-and-a-half orbit.

It’s different than geostationary weather satellites, which orbit at an altitude of 22,300 miles and appear to remain fixed above a certain point on the equator.

Geostationary satellites can’t see Alaska’s North Slope or the Arctic Ocean at the North Pole very well. Polar orbiting satellites, however, don’t have that problem.

Dr. Mitch Goldberg, JPSS program scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said the satellite has five instruments that are all extremely accurate.

The Joint Polar Satellite System-1 (JPSS-1) satellite, the first in a new series of four highly advanced National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) polar-orbiting satellites, is scheduled to launch on Tuesday, November 14, from Vandenberg Air Force Base, California. Learn more here

“If the atmosphere has a temperature change of, let’s say, just a tenth of a degree, which is important to be able to forecast weather, these instruments can sense that change,” Goldberg said.

One instrument includes a Day-Night Band. Basically, it’s a high resolution camera that can pick up visible light at night and see things in the dark, like clouds, smoke and fog.

Nate Eckstein, science infusion and technology transfer meteorologist for the National Weather Service in Alaska, said such visible imagery is very important for a state with long winter nights.

“It gives us great detail to see hazards for aviation like fog in a mountain pass before the sun comes up,” Eckstein said. “To get that into the forecast or warn a pilot, many of whom in Alaska are general aviation.”

Visual flight rules require pilots to see where they are going, and they cannot fly through clouds.

“This ability to detect small areas in tight places where our general aviation aircraft are operating is really key,” Eckstein said.

Infrared imaging used by many current weather satellites cannot distinguish between snow and clouds. They both show up as white in the image.

In addition, cloud cover in Alaska may obscure important marine or land details for days, even weeks at a time.

Eckstein has an example of how the satellite’s microwave instruments will be useful to the Bering Sea fishing fleet trying to avoid sea ice.

“Traditionally, I know sea ice analysts would get lots of satellite imagery as one of their primary tools,” Eckstein said. “A lot of it would get discarded because there’s stratus, clouds covering the sea ice edge and therefore they have to go back and use some older imagery to know that’s at.”

“Now, with microwave technology, we have the capability to see through these clouds in a lot of cases and know where the ice edge is on a more consistent basis, which leads to more accurate forecasts,” Eckstein said.

The satellite can provide an earlier warning of developing storm systems in the Western Pacific Ocean, increasing the accuracy of long-range forecasts.

Edward Liske, meteorologist and satellite focal point at the National Weather Service office in Juneau, said the new satellite also will provide more information about Alaska at a higher resolution. He said it’s going to provide a lot more data for the numerical models that generate forecasts.

“It’ll hopefully make those numerical models preform a lot better and be able to bring forecast systems more accurately and more in advance than what we currently have,” Liske said.

Warnings about wildland fires, ice jam flooding or heavy rainfall can also get to key decision-makers sooner.

JPSS-1 is a more robust version of NOAA’s Suomi research satellite that was pressed into operation after a successful demonstration six years ago.

The new satellite was supposed to be launched this Friday, November 10 from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, but that’s been pushed back until next Tuesday, November 14. Once in orbit, the satellite — renamed as NOAA 20 — will be checked out for 90 days before it’s put into operation.

Three more polar orbiting satellites in the series will be launched in the next several years.

Article from KTOO Public Media